In Alaska, a low-tech solution helps the ground stay cold enough, for now

FAIRBANKS, Alaska—While the world debates the causes of climate change and what, if anything, to do about it, Alaskans are busy dealing with its consequences.

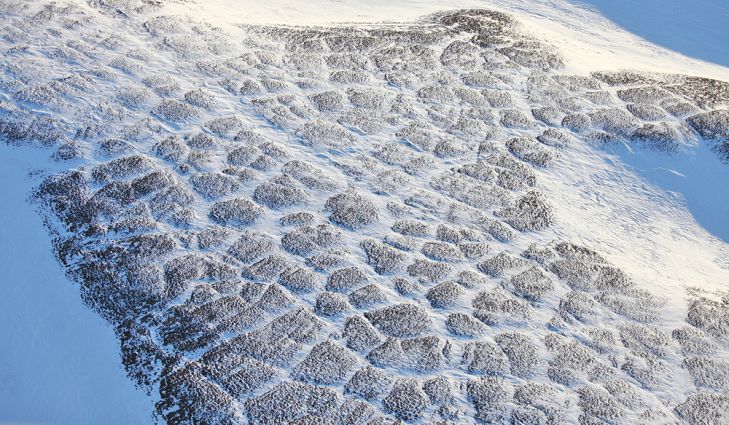

Permafrost, the frozen ground that lies just beneath the surface in most of the state, has become less stable in many areas, thanks in part to higher average air temperatures. It has begun to thaw in the warmer months and refreeze in the winter, causing shifts that wreak havoc on the structural integrity of the pipelines, railways, roads and buildings that sit on top of it.

“If we’re going to build on frozen ground, we want to keep it frozen,” says Dan White, director of the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

The Journal Report

See maps tracking Alaska’s ground temperatures since 1950 (Adobe Acrobat is required)

And see the full report: “Changes to Permafrost in Alaska: Observations and Modeling” (Adobe Acrobat is required)

To do that, engineers increasingly are turning to a low-tech solution: devices called thermosiphons that draw heat out of the ground. It’s a solution that shows how effective even relatively simple ingenuity can be in the absence of a more comprehensive, policy-driven response to climate change. But Alaska’s experience also shows the limits that such stopgap measures often run up against.

Alaska’s permafrost has been degrading since 1982 amid record warm temperatures, according to a 2006 study funded by oil giant ConocoPhillips. Milder winters are keeping the permafrost in many areas from getting cold enough to stay frozen during summers that are also getting warmer. Between 1949 and 2007, average annual temperatures in Alaska rose 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit, including an increase of 6.3 degrees in the winter, according to the Alaska Climate Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Development worsens the problem by stripping vegetation, an effective insulator, from the surface, replacing it with heat-absorbing man-made materials or leaving the ground bare.

With permafrost thawing and refreezing in more of Alaska over recent years, highways and railroad tracks have to be constantly repaired because of cracks, heaving and sinking. All around Fairbanks, homes can be seen listing on foundations that have been unsettled as the permafrost underneath them has thawed, and buildings in many other parts of the state have the same problem.

That’s where thermosiphons come in. The device essentially is a tube filled with gas that can’t escape. Part of the tube is buried in the ground, with the top exposed in the air. As temperatures plunge in the winter, the gas condenses into a liquid and falls to the bottom of the tube.

Thermosiphons protrude out of support beams on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Jim Carlson/The Wall Street Journal.

Heat Release

The relative warmth of the ground then causes the liquid to evaporate back into gas that rises to the top of the tube, where the heat it carries is dissipated into the air. The cycle keeps repeating itself, with no need for any kind of power source or any intervention other than maintenance. Scientists say the process cools the ground around a tube so much during the winter that it stays frozen even in summer.

Branching Out

Thermosiphons have been around in the Arctic for about 50 years. For most of that time they weren’t used much outside of large infrastructure projects like the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which is outfitted with about 120,000 of them. But they have been deployed more widely in recent years.

Arctic Foundations Inc., a company that specializes in ground-freezing systems, says its annual sales of the devices have jumped 50% over the past five years as it has installed them in hundreds of places in Alaska, including around schools and water tanks. The company, based in Anchorage, Alaska, has even used the devices as fence posts, since fences anchored by the usual kinds of posts are frequently “frost-jacked,” or driven out of the ground by shifting soil, says Ed Yarmak, the firm’s chief engineer.

One of the heaviest concentrations of thermosiphons is around Fairbanks, a metropolitan area of about 100,000 people. Among other uses, the devices ring a Federal Aviation Administration building, are stationed near utility poles and transmission towers, and have been installed along various roads in the area. On a one-mile stretch of Thompson Drive near the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus, engineers from the school put in a thermosiphon demonstration project five years ago. The devices are working as designed in keeping the ground frozen, says Doug Goering, dean of the school’s college of engineering and mines.

One of the heaviest concentrations of thermosiphons is around Fairbanks, a metropolitan area of about 100,000 people. Among other uses, the devices ring a Federal Aviation Administration building, are stationed near utility poles and transmission towers, and have been installed along various roads in the area. On a one-mile stretch of Thompson Drive near the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus, engineers from the school put in a thermosiphon demonstration project five years ago. The devices are working as designed in keeping the ground frozen, says Doug Goering, dean of the school’s college of engineering and mines.

The devices are being used in other Arctic regions, too. Arctic Foundations of Canada, an affiliate of the Alaskan company, says its sales of the devices have tripled over the past five years. That’s partly because the thermosiphons have proved useful in shoring up structures in the many mines that have been opened in the Canadian Arctic in recent years, says John Jardine, president of the affiliate. Similar devices are being deployed in Russia and China, where they are helping stabilize the Qinghai-Tibet railroad.

Cost and Maintenance

While thermosiphons have proved effective, they aren’t foolproof. Like any device, they sometimes malfunction. Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., an Anchorage-based company that operates the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, long ago embarked on a program to make sure that thermosiphons all along the pipeline keep working. Alyeska crews on the ground inspect the pipeline, using infrared cameras to scan the devices. If the telltale glow of heat being released is too dark, that indicates a gas blockage that may need repair.

In all, Alyeska has had to repair about 16,600 of its thermosiphons since 2001, or about 14% of the total, says Michelle Egan, an Alyeska spokeswoman.

Thermosiphons flank a Federal Aviation Administration building in Fairbanks, Alaska. The devices help keep the permafrost frozen beneath buildings and infrastructure in Alaska by transferring heat out of the ground. Jim Carlton/The Wall Street Journal.

Also, while the use of thermosiphons has surged, cost is an issue for many users and potential users. The devices are available in different sizes, but typically each one cools an area no more than about 10 feet in diameter, so it can take many of them to protect a structure. To shore up a home with nine of the devices would cost around $20,000, and protecting infrastructure on a massive scale is of course far more expensive.

As a result, thermosiphons are being used strategically. For example, 14 of the devices were installed by Alaska state highway officials along a stretch of Chena Hot Springs Road outside Fairbanks about 16 years ago. The reason: The location lies at the bottom of a hill, where there is more permafrost, and so more permafrost-related problems, than in many steeper places, says John Zarling, professor emeritus of mechanical engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“It’s too costly to protect the whole world,” Mr. Zarling explains. “So you pick the problem areas.”